Did you know that you can navigate the posts by swiping left and right?

Antarcticans Have It Better Than Us

03 Oct 2018

. category:

thoughts

.

Comments

#neuro

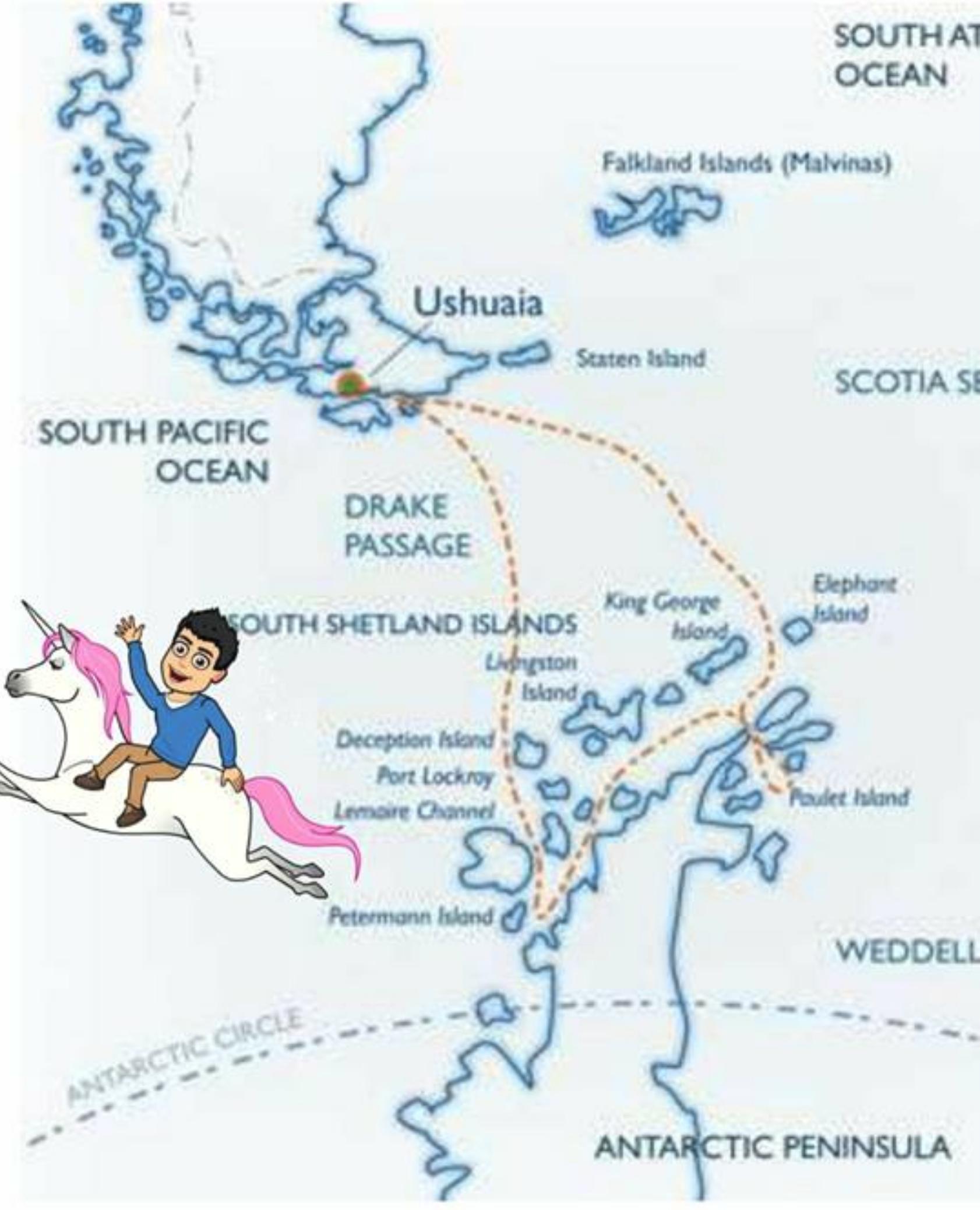

I’m not sure when my parents fell in love with the serenity and purity of icy places, but I was lucky enough to be dragged along for a family adventure to the frozen desert of Antarctica. Before departure, I picked up Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind as recommended by a classmate. The book not only kept me entertained on the 4 day round trip crossing Drake’s Passage, it also confirmed the feeling of bewildered alienation I had throughout the trip. Humans often boast about how big our brains swelled over 3 million years, but after interacting with the Antarctican wild life for two weeks up close, I can’t help but wonder if the gyrus folds in our cortex are taking humanity down the wrong path.

I’m not sure when my parents fell in love with the serenity and purity of icy places, but I was lucky enough to be dragged along for a family adventure to the frozen desert of Antarctica. Before departure, I picked up Yuval Noah Harari’s Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind as recommended by a classmate. The book not only kept me entertained on the 4 day round trip crossing Drake’s Passage, it also confirmed the feeling of bewildered alienation I had throughout the trip. Humans often boast about how big our brains swelled over 3 million years, but after interacting with the Antarctican wild life for two weeks up close, I can’t help but wonder if the gyrus folds in our cortex are taking humanity down the wrong path.

With the help of Dr. Harari, let’s quickly set up the scene: a single female ape had two daughters six million years ago, one became the ancestor of all chimpanzees, the other became our ancestor. Then two million years ago, earth became home to several human species. Things get interesting when our evolving biological machinery decided to shift resources from building muscles to neurons, meaning we couldn’t compete against chimpanzees for food unless we outsmarted them. Eventually, around 70,000 years ago, our brains became big enough to retain languages, transfer information, and build cultures. Humans decided to believe in rules, religions, and currencies of trade to keep their growing communities in tact as agriculture became their main method of sustaining life. Within a relatively short period of time, the frail relative of chimpanzees made a leap to the top of the food chain. The earth’s ecological system had always been able to regulate its species so no one destroyed the delicate balance of life, but the humans rose so rapidly that both the ecosystem and humans ourselves failed to adjust.

Antarctica on the other hand, has no native people, and remained uninfested until humans decided to commercialize oil. The frozen desert continent is capped by an inland ice sheet up to ~5 KM thick, containing about 70% of the world’s fresh water. The massive ice sheet is heavy enough to push portions of land below sea level, as well as raise Antarctica to have the highest average elevation of all continents. The Antarctic Treaty of 1959 banned all military and industrial activity in the continent, and reserved the untouched 180 million years old pristine continent for scientific research.

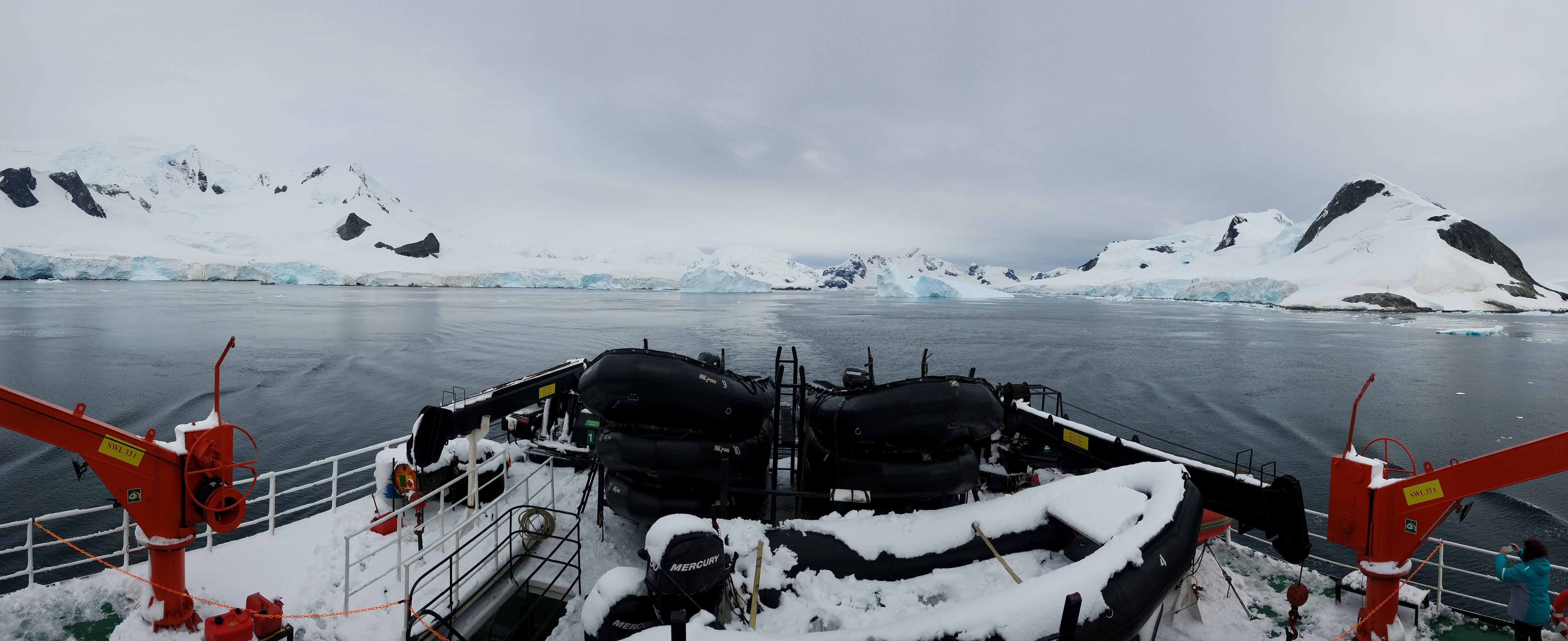

Tourists are allowed during the warmer summer months, and the door to the continent is only open to those willing to endure a 4 day round trip riding the violent waves of Drake’s Passage (As if mother nature is telling us: humans don’t belong here). The golden rule when landing in Antarctica is “bring nothing, take nothing”. To avoid ruining the ecosystem of Antarctica, we replaced our warm boots with sanitized rubber boots everyday, checked our jackets’ velcro tapes for any loose particles, and made sure we leave little to no impact on any landing. Our retired scientific vessel carried a professional crew full of wild life academics on sabbatical, they ensured our landings did not interfere with wildlife, had fully mapped out fissures hidden beneath the snow, and located shores that are safe from rising waters caused by avalanches/falling glaciers.

Upon arriving in the calm waters and finally seeing land, the freezing wind rudely slaps you across the face in an attempt to arouse you from the seasickness-induced lethargy. It didn’t take long for me to realize that all the merit badges from the Boy-scouts could not teach people what the words “nature” and “wildlife” truly meant. At first, the flowing glaciers, low hanging clouds, and the tranquil silence shroud the animated lives of the Antarcticans. Then, the occasional spying whale or hunting fur seal reminds you just how well evolution had engineered the engines that are turning the food chain. The frozen desert is actually full of intelligent lives.

Flora

Antarctica slowly drifted apart from South America and Africa around 180 million years ago, bringing a variety of warm climate species to the South Pole. As the continent was drifting, it became less probable for penguins to be threatened by large land mammals, so they traded its ability to fly and adapted to swim in the freezing waters instead. While it is easy to appreciate how these evolutionary traits made penguins a successful species in an extreme climate, people rarely think of flora as an intelligent and successful species. Sure plants didn’t invent refrigeration or fiber glass, but some will argue that plants are more intelligent and effective than humans in terms of survival.

People tend to forget that plants lack brains entirely, yet they are able to thrive in just about every corner of the earth, be it above or under water, including Antarctica. Advancements in genetics and molecular biology revealed the signals and receptors plant cells use to assimilate information and respond on the whole plant level. The molecular and electrical signals they use are identical to our own neurons to some extend, but yet, plants don’t have brains or act like they do. The Antarctic flora senses a wide range of variables unperceptable to humans, and makes complex decisions to maximize their exposure to free water and sunlight. In our limited vocabulary, the word nature indirectly excludes humans, this translates directly into our point of view from the top of the food chain: we rarely include ourselves as the object of study in nature. Therefore it is even more difficult for us accept that we are animals, and we need to move around to feed on others, that we have a lot to learn from plants that feed, grow, and reproduce while staying still.

Fauna

Like I mentioned before, homo sapiens are an extremely young species, we’ve only been around for 200,000 years. The efficient and powerful predators in Antarctica have been around for 350 million years. Perhaps, we have a lot to learn from the Antarcticans when it comes to being a predator.

Sure humans are at the top of the food chain, but in Antarctica, whales, orcas, and fur seals are as well. They prey on krill, fish, and even penguins without any rivalry. Yet, they live very discreet lives. In fact, whales and orcas are so discreet that scientists have trouble tracking them. These animals also find the most effective way of hunting, killing their targets in the flash of an eye. Evolution has taught these predators to not waste energy on excess, and they control their predatory powers.

It is unfortunate that humans have repeatedly chosen to abuse their position at the top of the food chain. The imagination and creativity provided by the larger than average cortex have ironically turned us rather unintelligible. Millions of years as the top predator in a stable environment made Antarcticans highly confident creatures, humans on the other hand, were just recently the underdogs of the South American jungles and African savanah. Our imagination quickly turned into fear and anxiety, turning us undoubtly cruel towards others and extremely dangerous. Just recall all the deadly ecological disasters we’ve caused, my favorite example of this is how Australia was once an incredible fauna for dinosaur sized mammals before humans arrived.

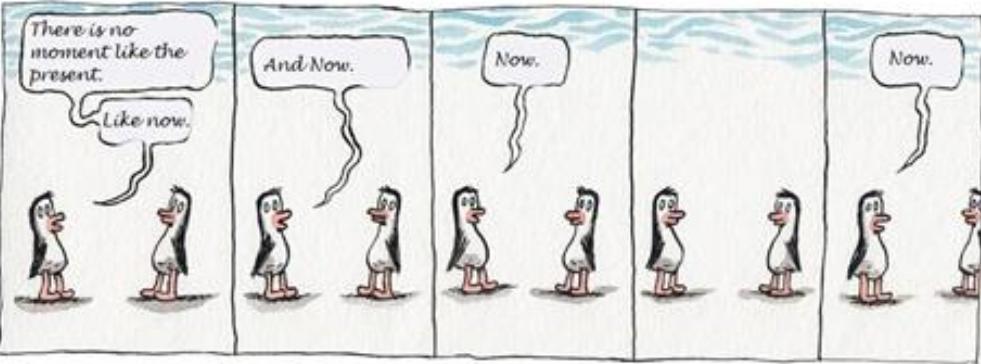

It is known that smaller verterbrates with brains containing about 100,000 times less neurons than ours have working memories, they can distinguish different signals, have social structures, and plan their actions. Humans surely do these things particularly well with the help of a larger brain, but these enhancements come with trade-offs. While observing the Antarcticans for two weeks, I couldn’t help but realize how every single creature except the humans are comfortably living in the present. I believe I am speaking for every single reader when I say that we are constantly worried about things we cannot control. Anxiety and depression are huge problems for the contemporary society, humans are always trying to prepare for the next event, coping with events from the past, chatting about what-ifs. On the other hand, birds have an incredible sense of spatial and temporal awareness, yet they only care about now. Nature’s intelligent design has engrained within penguins’ brains their ability to find their nest and babies within a massive colony after weeks of feeding far away at sea. It’s even more stressful for these birds when you factor in the climate, the predators, and the everchanging landscape in Antarctica. Somehow, these creatures are never anxious about anything! They can relax on the beach a few feet away from a fur seal as long as they are not being hunted, they will casually stroll to the waters when they are feeling hungry, and they will come up to humans when they feel curious. Yet, humans can’t enjoy a meal without checking their smartphones, can’t have a conversation without what-ifs, and if an alien species showed up, most of us would freak out like it’s the end of the world.

Being Human

Our ancesters had relatively small brains compared to us, yet they used 4 legs to walk and support their weight. Sapiens had to pay extra to support the larger brain’s weight while standing upright on 2 legs. The most obvious problems are neck and back pain, what’s not obvious is that our guts became smaller and more efficient as we started fires and cooked our food so our brains can consume more energy (Story for another day: our gut is our second brain). Women had to sacrifise even more for the bigger brain. Sapiens stood up with narrower hips, meaning a smaller birth canal for babies, and death during childbirth became a hinderance. So along the lines of Darwinism, evolution favored women who gave birth earlier since the infant’s brains were smaller and “squishier”. Compared to other species, humans are born prematurely, when their immune and locomotive systems are still under-developed. Human babies are helpless compared to whales and seals that swim shortly after birth. Most mammals are born intelligible enough to interact with nature, whereas humans require years of protection and nurture. It is also no surprise that penguin colonies have no idealogical conflicts whereas humans are being molded into religious fanatics, war mongers, and capitalists.

Today, humans are practically playing god. We’ve created machineries to harness everything nature has to give, increased food production to unsustainable levels, our medical practices often trespass what’s considered sacred by nature. Yet we remain unsure of our goal as a species, we seem extremely unsatisfied despite our exploding population and nobody knows where we are going or what to do with our accumulated power.

A direct quote from Sapiens: “But did we decrease the amount of suffering in the world? Time and again, massive increases in human power did not necessarily improve the well-being of individual Sapiens, and usually caused immense misery to other animals.”

Humans have become the most irresponsible predators, continuously destroying our ecosystem without an end in sight. Humans are related to other species, and we eat them to live, should we be responsible for these species? Our predative nature is enhanced by technology, knowledge, and ideas, but we are the least intelligent predators in nature. By understanding ourselves as animals, by understanding other species as intelligent, and by understanding the intelligence of predators, perhaps, we can transform ourselves into intelligent predators.

Books I referenced, occasionally paraphrased, and took inspiration from, highly recommended readings if this stuff sparked something in you:

-

Narby, Jeremy. Intelligence in Nature: an Inquiry into Knowledge. Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin, 2006.

-

Harari, Yuval N., et al. Sapiens: a Brief History of Humankind. Harper Perennial, 2018.

Instagram post with more Antarctic wildlife photos: