Did you know that you can navigate the posts by swiping left and right?

Why you should use LaTeX for your thesis and manuscripts

06 Jan 2022

. category:

thoughts

.

Comments

#neuro

#academia

I refused to read a 6 page PDF full of numbers and jargons posted by the graduate school to format my thesis. The most insane thing is, the graduate school would rather provide an example document in PDF than to provide a usable template, not even as a Word document. Why should graduate students suffer through hours of formatting when they should be focused on writing? Why should every student repeat the same suffering when a template would save everyone an incredible amount of time and stress?

While Weill Cornell Medicine doesn’t provide usable templates on their graduate school website, a little digging turned up Cornell University’s website which includes a LaTeX template. Turns out the medical branch of Cornell uses the same formatting requirements as the main campus in Ithaca! With a few necessary modifications, I was able to submit my Ph.D thesis without worrying about formatting at all. My committee chair then asked me if it’s possible to provide a lightweight template for the graduate school to share with all students, so I started another GitHub repository and combined the Cornell University template with examples from bioRXiv’s LaTeX template to create wcm-thesis-template. Feel free to dig around in there and adapt it for your own thesis!

Since I finished my thesis defense, a few students with the same complaints about thesis formatting approached me about my LaTeX document. Not only did LaTeX help them write more efficiently, they also realized how inefficient Microsoft Word is compared to LaTeX. So here I will list out the main reasons why academics working on manuscript or thesis documents should adopt LaTeX for their own benefits.

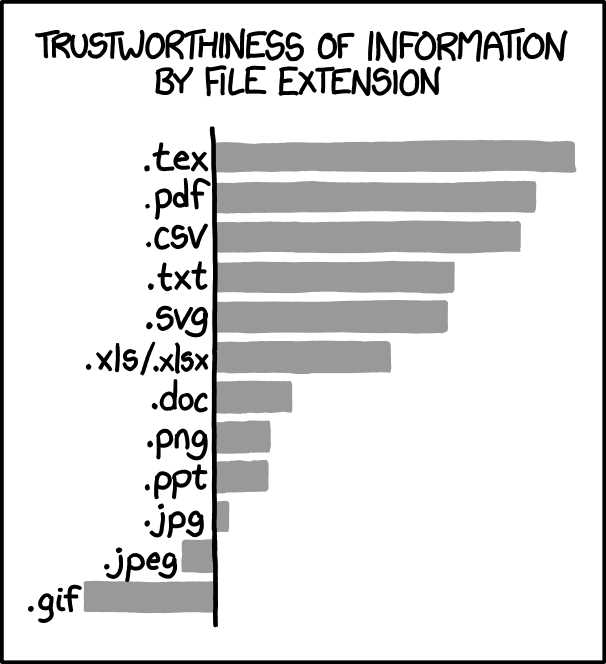

Not all texts are created equal

Most bench scientists with no coding experience do not realize the characters showing up in a Word document are not the same as plain text documents. Microsoft Word is a clever feat of software engineering, it removed the gap between plain looking text passages and a fancy formatted paragraph with selected fonts and styles. But to achieve this, the texts in Word documents have lots of functioning code that are hidden away from the users. This is why Word has compatibility warnings if you try to open other types of text files in Word, or sometimes you see gibberish symbols if you opened a document with unknown fonts or language characters.

If you are friendly with your computer’s Shell commandline (ther Terminal for Mac users), you can try to print out the first line of a .docx file with head -1 wordfile.docx, your computer will print out a bunch of gibberish (the embedded fancy codes in Word). But if you did the same thing with a LaTeX .tex file, you will see the plain text from the first line of the document:

$ tree -h

├── [135K] References.bib

├── [ 14K] cornell.cls

├── [ 50M] dissertation.pdf

├── [8.2K] dissertation.tex

└── [5.2K] hangcaption.sty

$ head -1 dissertation.tex

\documentclass[phd,tocprelim]{cornell}

In the above example, I first showed the files in my thesis folder and their file sizes with tree. Notice how a 8.2KB .tex file made a 50MB PDF. Then I printed the first line of my thesis text file with head -1, which declared my LaTeX file to use the formatting as specified by the cornell.cls class file. So instead of encoding the text contents and the styling in the same file as in a .docx file, LaTeX’s .tex file is a plain lightweight file, and all formatting is declared in a separate .cls file.

The clear benefit here is that you only modify the lightweight plain text file, your text editor will not take forever to save or stutter/crash due to computer memory problems. Additionally, differently styled sections of your document is pre-defined for you, you simply enter your biosketch or acknowledgements under each section and they will be styled appropriately respectively when you compile the PDF document for viewing.

These class files are always provided with LaTeX templates, people rarely create their own templates from scratch now that resources like overleaf have gathered all sorts of templates. Academic publishers have made their LaTeX templates available online as well, scientists can even submit LaTeX projects directly from overleaf to a journal. Need a manuscript template for Elsevier? Want to build a pretty looking resume? Just look it up online and fill in the blanks! Then have your collaborators jointly edit the manuscript online without having to email each other documents titled “manuscript_122422_final_revised_xx_edited_figureupdated.docx”.

Love your keyboard, stay away from your mouse

Handling Word documents require you to memorize a bunch of keyboard shortcuts, or you need to stop typing and navigate the user interface with your mouse. For example, citing an article from a citation manager requires installation of a plugin and clicking through a series of menus. I’ve personally had terrible experiences with these plugins being slow or crashing.

LaTeX on the other hand, you can export all the articles you need as a bibtex file (References.bib), and simply type \cite{article_title} as you are typing, no mousing around needed. Want to insert some math symbols like $\lambda$? Don’t bother looking for Greek letters in some equations dropdown menu, simply type $\lambda$. Want to display a figure or a large equation? Then create an environment with \begin{figure} or \begin{equation}. Instead of manually dragging and resizing figures, you can direct the figures by declaring {width=0.5\textwidth,right} to scale a figure according to your document’s text width and align it to the right. This all done with plain texts, no fancy markups resulting in your document exploding in file size.

Linking your content

After declaring your figures, equations, or titled sections of text, a label can be easily assigned with \label{}. For example:

% A chapter:

\chapter{Introduction}

\label{chap:intro}

% A spiral image labeled fig:spiral

\begin{figure}[h]

\includegraphics[width=0.5\textwidth]{spiral}

\label{fig:spiral}

\end{figure}

These labels can then help you link text to your content. While writing your conclusions, you might want to refer to the spiral figure from your introduction chapter, and you can simply say “As shown in Chapter \ref{chap:intro}’s Figure \ref{fig:spiral}”. Not only are sections automatically numbered for you in the final PDF, the in-text \ref calls are rendered as hyperlinks, so that clicking on “Figure 1” in text will navigate to where the image is displayed in your large PDF document.

As you finish compiling all chapters, subsections, and graphics in your document, creating a table of contents and list of figures right after your title page is as simple as:

\tableofcontents

\listoffigures

\listoftables

These commands will find all the sectioned contents you declared throughout your .tex files and automatically sort them into neatly organized lists. Each entry in these lists are also automatically linked to the locations of respective figures, tables, and chapters.

Handling your bibliography

A friend of mine had an old professor share a .docx document with a Word generated bibliography and asked her to move and combine the references into another document. Without realizing that Word bibliographies are not editable objects. I had to find an online tool to convert the .docx references list to a .bib file so she can import the new references into her citation manager, and then finally insert into a new document.

With LaTeX, simply export all your citations to a single .bib file, \cite them as you write, and then write \bibliography{name-of-your-bib-file} at the end of your document to create a pre-formatted bibliography. You don’t have to worry about wrongly numbered citations, you can see exactly what’s cited as you write, and you can edit citation information in the entries of your .bib file as you please. No contents are locked behind layers of code unknown to the users.

Will I ever use Microsoft Word again?

Maybe, but it is behind a paywall, whereas LaTeX tools are open source projects. I got a new personal laptop after returning my lab’s laptop to my professor, and I haven’t felt the need to pay for Microsoft’s software suite. I see the appeal of Word when working with small documents, like a short cover letter. It’s nice to immediately see the outcome of your writing. But other than that, I see no other outstanding feature that would make me want to pay for it. I also did joke with my friend that I refuse to work with people that share Word documents or Excel spreadsheets with me. And I hope my future job search lands me in a computer savy team that appreciates simplicity.